By: Madaline George

Constitutional term limits on a president’s tenure are common features in modern democracies. Seventy three percent of all presidential regimes at the end of 2009 used some form of presidential term limits, and in Africa two-thirds of countries employ such limitations. Term limits are a tool that help ensure periodic turn-over of power and, if adhered to, prevent the emergence of “electoral dictatorships” or incumbents becoming pseudo-monarchs.

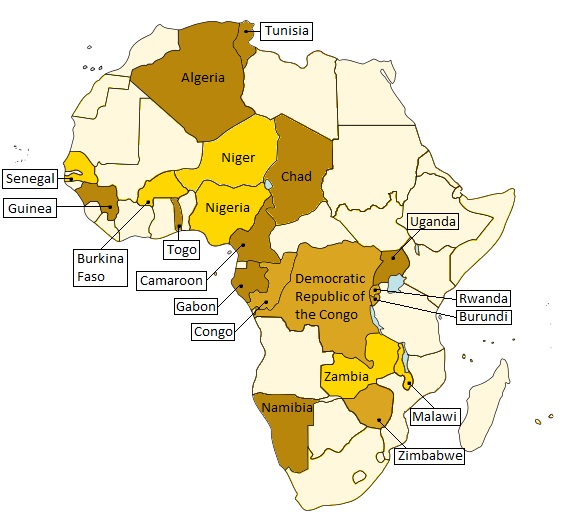

Map of Africa with select countries filled in according to their inclusion in the present blog post.

Survey data indicates that there is strong support for presidential term limits among Africans, even in countries that have never had term limits and in those that have seen them recently removed. But examples abound of incumbent governments attempting to forgo such limits and extend their rule. Although some have failed, notably in Zambia, Malawi and Nigeria, about half of the African countries that only recently embraced this democratic tool have seen it removed from their systems. While this is not an African anomaly – examples can be found in Latin America, Eastern Europe and Asia – it is of critical importance in the Central African region today.

Since the 1990s, several African countries have amended or manipulated their constitutions to extend a president’s rule, including Algeria, Cameroon, Chad, Gabon, Guinea, Namibia, Togo, Tunisia (although the 2014 Constitution reinstated term limits) and Uganda. These moves are often done through a legislative body, judicial decree, or by public referendum, and often in places where confidence in the free and fair nature of elections is low.

Sometimes attempts fail. Burkina Faso’s president, Blaise Compaoré, who ruled the country for 27 years, was forced from power in 2014 after his attempt to extend his constitutional mandate was met with mass protests. Senegalese president Abdoulaye Wade lost the election in 2012 even after using the constitutional court to interpret a legal technicality to allow him to run for a third term. And in 2010, an attempt to extend term limits in Niger resulted in a coup.

But almost universally, such a move, successful or not, is accompanied by violence and the suppression of political expression. Burundi, which only 10 years ago saw the end of a brutal civil war that killed more than 300,000 people and displaced more, has been plunged into violence, chaos and political unrest following the April 2015 announcement by President Pierre Nkurunziza of his intention to run for an additional term, and his subsequent election in July. African Union Commission chief Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, speaking recently about this situation warned that, “the real risk of seeing a further deterioration with catastrophic consequences both for the country itself, and for the whole region.”

Joseph Kabila Kabange, President of the DRC, speaking in front of the UN General Assembly. Source: United Nations.

With elections in nearby countries with long-standing rulers approaching, the risk of further regional destabilization is increased. The absence of, or failure to adhere to, term limits can be a catalyst for state failure and collapse. It will be increasingly important for states to abide by their constitutional mandates where the democratic experiment is still young and fragile.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is scheduled to host elections in 2016. This will be the first time power could change hands since the assassination of Laurent Kabila in 2001, father of current President Joseph Kabila Kabange. The DRC Constitution limits a president to two five-year terms (article 220). Kabila has been in power for 14 years. He ruled for five years without a democratic mandate following his father’s assassination and in 2005 won the first free Congo elections since independence from Belgium in 1960. His second term came through disputed 2011 elections. But many wonder if Kabila, 43, plans to stay in power.

There were three days of protests in January 2015 against a draft bill that would have temporarily allowed Kabila to extend his term that left at least 40 dead and dozens wounded. Many, including opposition leaders, were arrested. A more recent peaceful student protest was violently broken up. The government ordered the shut down of the internet in some instances to immobilize protesters and limit media. Even leaders (deemed the G7) in the ruling alliance signed an open letter urging respect for term limits; they were subsequently expelled from government. The UN and human rights organizations have expressed concern over the attacks on the freedom of political speech and association.

This pattern of serious human rights violations, including state violence, intimidation, arbitrary arrests and detentions and the suppression of political opinion and association has played out in this region before. If Kabila refuses to relinquish power, it is likely to set off a violent chain reaction in the fragile central African region.

Upcoming elections in nearby states could also challenge the rule of long standing leaders. Congo (Brazzaille)’s 2002 Constitution, for example, limits a president to two terms (article 54) and the age of a candidate to no more than 70 (article 185). Despite this, Congo reported 92% voting in favor last month on a Constitutional referendum to allow President Denis N’Guesso, 73, to run for a third term. President N’Guesso has ruled Congo for 31 of the past 36 years. After losing the 1992 presidential election to Pascal Lissouba, the former military leader seized power back five years later after engaging the country in a brief civil war.

Yoweri Museveni, President of Uganda, at a campaign rally in 2010. Source: Daily Monitor.

In neighboring Uganda, Yoweri Museveni has served at the top seat of government for 29 years, and is expected to stand for a fifth term in in 2016. Although Museveni succeeded in getting the Parliament to remove term limits in 2005, the country is increasingly calling for their return.

In Zimbabwe, a new constitution enacted in 2013 limits presidential tenures to two five-year terms, but does not apply retroactively. President Robert Mugabe, 89, who has ruled the country since independence in 1980, could extend his rule for another 10 year term if he chooses to run in 2018.

In Rwanda, elections are scheduled for 2017. Despite the Constitutional limits that state, “[u]nder no circumstances shall a person hold the office of President of Republic for more than two terms” (article 101), a petition apparently signed by more than 3 million Rwandans requested a constitutional change to allow Rwandan President Paul Kagame to run for a third term. Despite opposition party efforts, Parliament voted to support this amendment in July of 2015, which was subsequently approved by voters in a national referendum in December. Kagame has since announced that he does in fact intend to seek a third term.

The absence of term limits may provoke violent opposition, the growth of rebel movements and coup d’etats, and human rights abuses. Term limits can assist in the peaceful transfer of power and contribute to the general peace and security of a country and region. How these elections are conducted and whether the democratic process of transferring power is observed will be of crucial importance for this region.